15-418 Final Project Proposal

High Performance Video Processing Suite For Autonomous Vehicles

Nishad Gothoskar and Cyrus Tabrizi

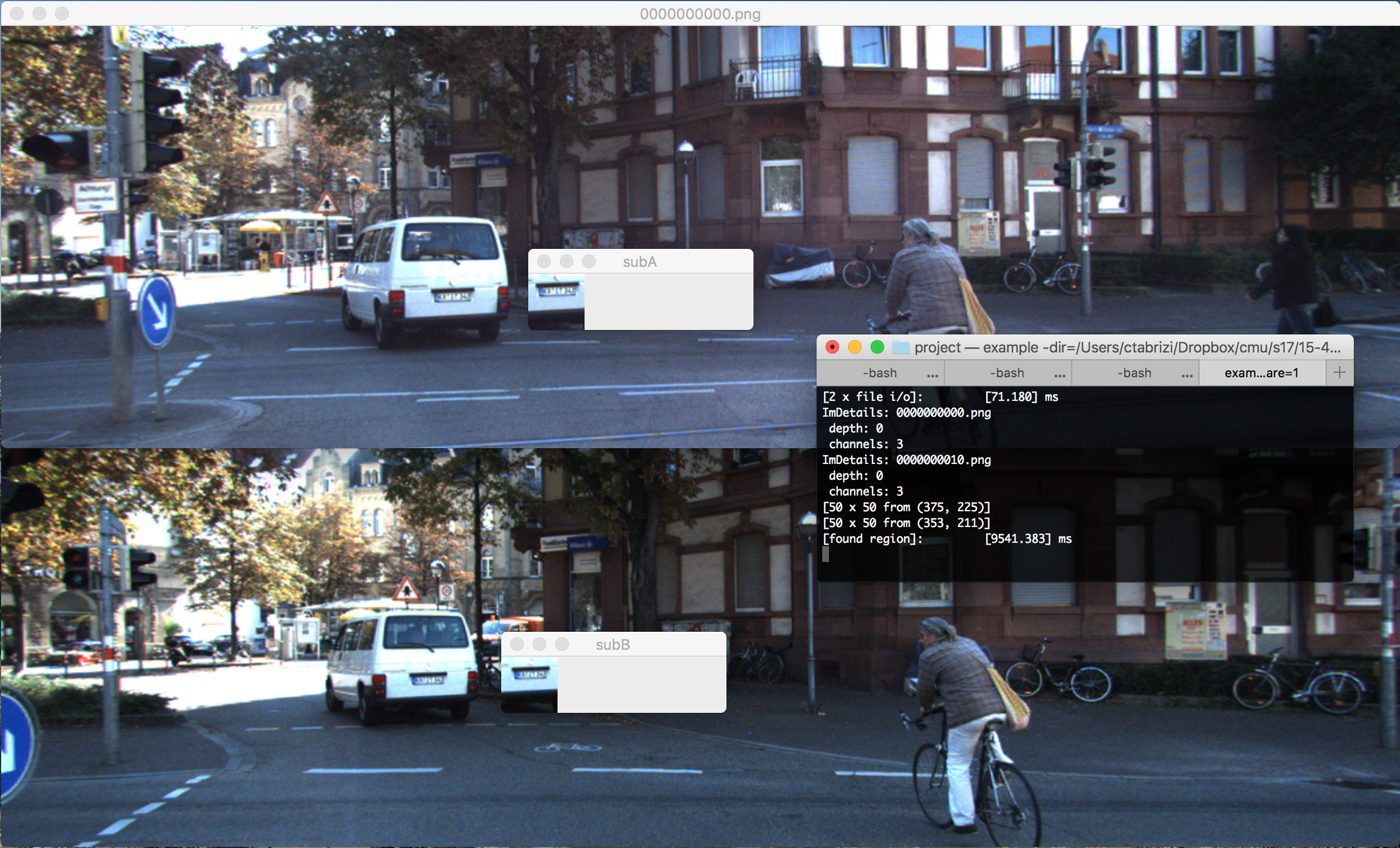

Figure 1: Naive CPU 50x50 pixel region matching across RGB images

Summary

We are going to build a set of parallel visual-computing tools for doing realtime processing of autonomous vehicle sensor data. The ability to efficiently process multiple streams of video and depth data in real-time is critical to the improved safety and performance of autonomous vehicles. Our suite will create versions of these algorithms specifically optimized for parallel operation in this compute-constrained environment.

Background

Autonomous vehicles use a number of RGB cameras and depth sensors to perceive the world around them. To make sense of all this data, a vehicle’s onboard computer passes each stream of sensor data through a real-time processing pipeline composed of both high-level and low-level stages. While the specifics will vary by vehicle, there are many low-level algorithms that are common across many contexts. The goal of our project is to implement a small set of these low-level algorithms in a way that leverages GPU hardware efficiently and satisfies the real-time constraints of an autonomous vehicle. There are examples of image-processing libraries (like OpenCV, VisionWorks) that are performant in both CPU and GPU-based environments, but we’re interested in applying our own understanding of CUDA and GPU architecture to implement these algorithms as best as we can.

The main set of algorithms we are considering working on are:

- Optical Flow: Tracking the velocity of different objects in a scene and producing a vector field at different temporal and spatial resolutions

- Convolution: Support for applying different kernels to color and depth images:

- Edge detection

- Blurring

- Sharpening

- Temporal and Spatial Resampling: Support different interpolation methods for compressing RGB and Depth data across both space and time

- Lens Distortion Compensation

- Subregion Statistics: Return variance, average, minimum and maximum values for a specific region of the data

- Image Segmentation: Identifying clusters of similar RGB or Depth data in a single frame

- Feature Correspondence: Evaluating similarity of two different images for the purposes of matching

All of these algorithms take imagery as an input and some return modified imagery while others return data about the imagery in a different format. The part of these algorithms that is computationally intensive is the application of potentially extensive logic to lots of data . Fortunately, lots of these algorithms are examples of data-parallel problems where the code executed involves the same logic repeated over lots of data. However, some of these algorithms also involve divergent execution or otherwise prominently feature bad cases of work imbalance or sequential logic. Additionally, many of these functions can be conducted in isolation from other frames but also take on a new meaning when used in the context of video, where the input for a given function call includes the current data frame as well as the outputs of processing the previous frame(s) of the video.

These algorithms will be packaged together to demonstrate their use in a fictional autonomous vehicle image processing pipeline using real RGB and depth footage.

The Challenge

Each of the low-level algorithms we plan to implement will feature a different set of challenges. Some of these algorithms are inherently parallel but will require a clean and efficient implementation to minimize latency and achieve real-time performance. Others make it more difficult to exploit that parallelism by involving large chains of dependencies and will require additional cleverness to optimize for a GPU. The goal of applying our 15-418 learning to these algorithms in this way is to further our understanding of the algorithms themselves as well as our ability to write GPU-optimized code.

Resources

We primarily intend to use the GPU’s in the GHC cluster but are considering using an NVIDIA Jetson TX1 to test these algorithms in a more constrained environment. We will also be writing the code from scratch but will refer to the documentation for the OpenCV and VisionWorks libraries to better understand the intended behavior of the algorithms themselves. The data set that we will use to test our processing pipeline on is a mirror of the Kitti dataset used in the Udacity Self-Driving Car Challenge 2017. The dataset contains the following (captured and synchronized at 10Hz):

- Raw (unsynced+unrectified) and processed (synced+rectified) grayscale stereo sequences (0.5 Megapixels, stored in png format)

- Raw (unsynced+unrectified) and processed (synced+rectified) color stereo sequences (0.5 Megapixels, stored in png format)

- 3D Velodyne point clouds (100k points per frame, stored as binary float matrix)

- 3D GPS/IMU data (location, speed, acceleration, meta information, stored as text file)

- Calibration (Camera, Camera-to-GPS/IMU, Camera-to-Velodyne, stored as text file)

- 3D object tracklet labels (cars, trucks, trams, pedestrians, cyclists, stored as xml file)

Goals and Deliverables

The deliverable is a demo application that displays each of these algorithms running in real-time in the example RGB and depth dataset. A side-by-side view will show the input data and the resulting data that is produced by the currently selected library feature.

In general, real-time performance means imperceptible to the human eye. This carries with it a specific latency time. In an autonomous vehicle, however, the standard is even higher as the algorithms need to reach super-human performance and are safety-critical in nature.

To evaluate our performance in this regard, we will constantly compare the performance of our code against industry standards like OpenCV and VisionWorks. Our current plan is to come within an order of magnitude of these implementations with respect to the computation time over a single frame and the latency observed over a video stream. Our stretch goal is to include additional function calls and also achieve real-time performance on a more constrained computer like the Jetson TX1.

Platform Choice

The code for vision pipeline will be written from scratch using CUDA. We chose CUDA for this project because of our previous experience using CUDA for image processing in Assignment 2 (Circle Renderer). In particular, we expect the shared memory aspect of that assignment will be particularly relevant in some of our implementations. We will run and test our code primarily on the GHC machines. We are purposefully using the GHC machines instead of more powerful ones in order to better model the restricted computational ability of current onboard autonomous vehicle computers.

Schedule

- Mon, April 10th (11:59pm) – Project Proposal Due

- Wed, April 12th – Import and read from KITTI dataset

- Fri, April 14th – Understand intended algorithm behavior, design library interface

- Mon, April 17th – Naive GPU implementation for each algorithm

- Tue April 25th (11:59pm) – Project Checkpoint Report Due

- Fri, May 5th – Achieve real-time on all original algorithms

- Wed May 10th (9:00am) – Project pages are made available to judges for finalist selection.

- Thurs May 11th (3pm) – Finalists announced, presentation time sign ups

- Fri May 12th – Parallelism Competition Day + Project Party / Final Report Due at 11:59pm

Checkpoint

Updated Schedule

- Tue April 25th (11:59pm) – Project Checkpoint Report Due

- Fri Apr 28th - Finish preliminary GPU implementation for each algorithm

- Mon May 1st - Complete first full GPU vs CPU benchmark

- Wed May 3rd - Push CPU and GPU versions closer to real-time

- Sat May 6th - Combine algorithms to build pipeline

- Tue, May 9th – Final performance tuning for pipeline, prepare video of demo

- Wed May 10th (9:00am) – Project pages are made available to judges for finalist selection.

- Thurs May 11th (3pm) – Finalists announced, presentation time sign ups

- Fri May 12th – Parallelism Competition Day + Project Party / Final Report Due at 11:59pm

Checkpoint Update

Progress has been made on four different fronts. The first component is a CUDA implementation of k-means clustering for 3D data points. This is important so that we can recognize the clusters as objects. To implement k-means, we’re using the standard iterative approach, but computing clusters and membership in parallel across points. Given that k-means requires that all computation for a stage is completed before the reassignment of clusters is done, a large amount of synchronization is necessary. The second CUDA implementation is of the Canny edge detection algorithm, Canny edge detection is also a key component of feature extraction on RGB image data. Canny edge detection involves applying Gaussian filters using convolution and then detecting gradient directions. These are just the first two steps in the process, but are highly parallelizable across pixels and regions. The third component has been feature comparison and feature matching across images. This feature enables us to identify the location of a given object across multiple frames. Combining this with our depth data will eventually enable us to build a map as we move through the scene. Currently, we’re able to evaluate a similarity score for a region in two different images as well as identify the region in one image that is most similar to a specified region in another. This has been implemented sequentially on a CPU without any data reuse and it is already clear what the first steps should be for optimizing the CPU version. The last component has been to set up OpenCV and a basic timing framework. Currently, the feature comparison and feature matching functions have been implemented inside of this framework, giving me an executable that I can run on various images and get timing values as a result.

The main thing that changed between our proposal and this checkpoint has been our shift from working on a set of independent vision functions meant for generic use on autonomous vehicle sensor data (functions like “Edge Detection”) to working on a vision pipeline that will specifically support real-time Simultaneous Localization and Mapping (SLAM) on that same autonomous vehicle sensor data. We knew from the beginning that we were interested in supporting some kind of vision work in autonomous vehicles but only now have we figured out the specific way we wanted to do that. Making this shift towards a real-time SLAM pipeline has been good for us as it helped us direct our efforts. Previously, when we knew only that we wanted to support a generic library of “real-time” vision functions, the “real-time” requirement was hard to define. Now that we know that those functions have to work together to support SLAM, we can determine exactly what timing requirements our pipeline must meet in order for the vehicle to stop given a map-based visual cue.

Our updated demo will show the sensor data at the original data capture rate and generate a viewable map at the same rate and within a latency that would allow a car to brake safely at the sight of an obstacle. Since we can’t collect our own sensor data and demo this on an actual vehicle, we will allow the data capture rate to be adjusted during the demo to simulate travelling at different speeds. Being able to control the data capture rate as we tune our pipeline further will allow us to estimate the resulting braking distance, which is the measure by which we’ll evaluate the performance of our GPU and CPU SLAM implementations. We’ll also make it possible to explore the resolution/performance trade-offs with our SLAM pipeline since it’s possible a lower-resolution map output might be an acceptable compromise to improve timing requirements.

The main issue we’ve faced so far was our unfamiliarity with the specific details of SLAM. Implementing SLAM on a short deadline required understanding enough about existing approaches to start working on its individual components without knowing exactly how those components would need to perform or behave once combined. It’s a risky pipeline to implement because we’re implementing and learning about both those individual components for the first time as well as the pipeline overall. Another issue is that our work on those individual components can only be evaluated meaningfully once combined into a working SLAM demo. The individual algorithms behind SLAM may be challenging and we’ll still be able to compare optimized CPU and optimized GPU versions, but without them working together, there won’t be anything particularly exciting to show for.

Even though we’re behind schedule according to our original deadlines, our decision to move towards a specific kind of functionality has helped us catch up. It’s still our intention to have a complete working demo by the competition day even though it’s unknown exactly what additional algorithms we’ll need to make SLAM work in real-time. This unknown is concerning but also exciting. At this point, it’s mostly a matter of getting the work done.